Inflation is running at its highest level over four decades and is forecasted to stay high and far above central banks' targets also next year. Central banks failed to deliver on their commitment to keeping inflation under control. Fed and ECB can only restore their credibility by acting aggressively to bring inflation down and compensate for their policy, forecasting and communication errors.

We argue that only a severe recession in the US, with a material rise of the unemployment rate, will bring US inflation down. For this reason, the Fed may have to increase rates even above 6 percent by the end of 2023, more than markets currently assume and more than forecasted by Fed officials in their September projections.

Fed's forecasts include a dot plot chart that shows what the Fed funds rate should be according to as many as 19 Fed officials, each contributing one dot. The dot plot has an abysmal track record in predicting what the Fed will end up doing. For example, just one year ago, Fed officials painted a very accommodative monetary policy stance, with the Fed funds rate forecasted at just 0.3 percent and inflation close to the 2 percent target for 2022.

This rosy picture has substantially changed since last year, as a number of factors – including less anchored inflation expectations, exceptionally accommodative monetary and fiscal policies, supply chain bottlenecks, labor shortages and higher commodity prices – led to high and broad-based inflation. Caught by surprise, the Fed has embarked on an aggressive tightening path, hiking interest rates to the current 3.0-3.25% level and starting reducing its $9 trillion balance sheet. For the philologists and the communication experts, Fed Chair Powell ditched the "transitory" tag only last November. Crucially, 12 out of 19 Fed officials now expect the Fed funds rate to be set between 4.5 percent and 5 percent by the end-2023 (see Chart 1), in sharp contrast to previous guidance.

Chart 1: Fed's Policy Metamorphosis IV – Tighter for Longer.

Beyond the plots, Fed's new guidance is clear: tighter policy for much longer. There should be little doubt about its determination to fight inflation over supporting growth or financial markets' dips.

More problematic is the question of how high the Fed funds rate need to rise to bring inflation down. Economic theory suggests that central banks can achieve the desired economic outcomes if the monetary policy responds in a predictable way to changes in economic conditions, as prescribed by standard monetary policy rules. Currently, a range of simple policy rules prescribes a value for the Fed funds rate at between 5 percent and 9 percent, based on realistic assumptions for inflation, real interest rates and economic slack. The rules prescriptions have materially risen since last year, as inflation readings climbed far above the Fed's 2 percent target and as the economy at 3.6 percent unemployment rate started overheating, putting pressure on inflation.

It is likely that a peak rate of 6 percent or even higher will be needed to bring inflation down to its target and to reverse economic overheating. Crucially, the Fed will continue this hiking path rather than stopping earlier, as it has to prove its determination to act aggressively to reduce inflation, eventually restoring its own credibility undermined by previous policy, forecasting and communication mistakes.

Central banks' credibility is closely connected to the institution’s performance and monetary policy success. Formally, credibility is defined as a commitment to follow transparent rules and policy goals. For this reason, credibility is a policy target in itself; and in Alan Blinder's words “…is built up by a history of matching deeds to words.” By rebuilding its credibility, dented by the late understanding and response to inflation, the Fed hopes to convince firms and workers, making decisions based on expectations, that it will achieve its 2 percent inflation target.

Still, the Fed hopes to slow GDP growth enough to relieve overheating pressures in the US labor market without rising unemployment and avoid pushing the economy into a recession. This outcome, the soft landing, has no chance of materializing. The main reason is the tightness in the US labor market, as measured for instance, by the current remarkably high number of job openings. According to Blanchard, the job vacancy rate has never before declined without a significant increase in the unemployment rate. Moreover, as the unemployment rate is at 3.6 percent, it needs to raise above the natural unemployment rate of 4.5-5.0 percent, as estimated by Blanchard, Domash and Summers, to bring inflation down. Simple computations based on Okun's law show that a severe recession is inevitable, with the desired rate of unemployment above its natural rate and the Fed holding to its resolve to fight inflation.

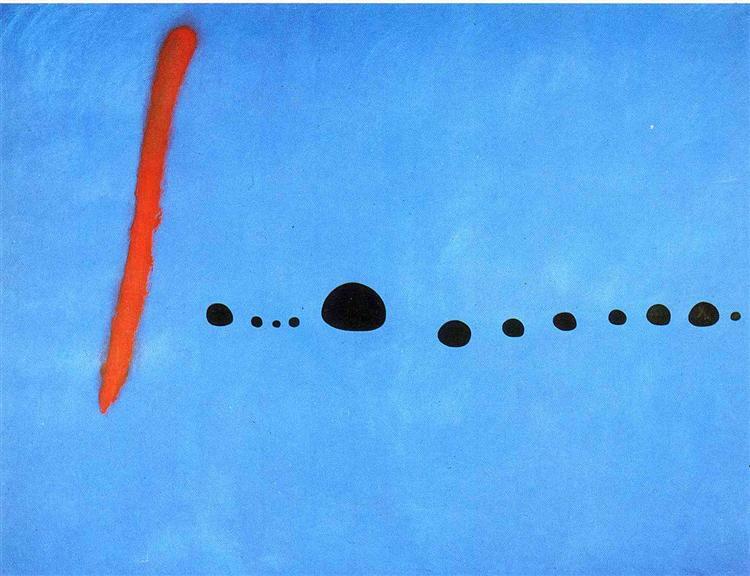

Surrealist artists mastered the art of balancing a rational vision of life with one asserting the power of unconscious and dreams. Expect a less Surrealist Fed in coming months, aggressively rising the fed funds rate and engineering a severe recession in the US, both needed to rebuild its credibility and to bring inflation down.