Apple's “Crush!” advertisement, which features the brutal demolition of various creative and cultural items to promote a new iPad model, evokes a world of constant innovation and disruption, leading to economic growth and better quality of life.

The impression is deceptive.

For starters, it is a fact that technological progress embodied in physical capital, intangible capital (ideas) and human capital (education) is the fundamental driver of economic growth, rather than the mere accumulation of labor and capital.

Recent economic models incorporate the idea that profit incentives drive entrepreneurs to innovate, so they create new products, processes, and business models that revolutionize industries and generate economic growth.

The idea is not new. In 1942, Joseph Schumpeter introduced a model of economic growth based on the mechanism of creative destruction, the process by which latest innovations render previous innovations obsolete. This cycle of destruction and creation is essential for economic progress and is intrinsic to capitalism. The dilemma of this growth process is that monopolistic rents are essential to motivate and reward innovative firms, but as these firms become monopolists, they obstruct the entry of new, innovative firms. Schumpeter believed that superstar companies would discourage and eventually push out smaller, innovative companies heralding the age of bureaucracies and vested interests.

Innovation waves

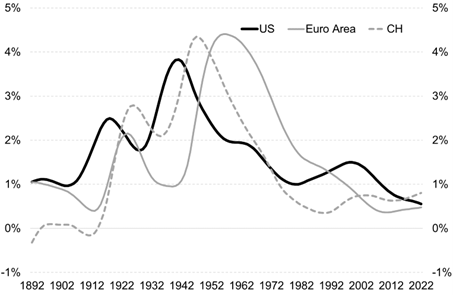

The invention of the steam engine in England in the 1770s revolutionized transportation and manufacturing, leading to unprecedented levels of growth in Europe followed by the US. Similarly, the introduction of electricity in the early 20th century laid the foundation for the extraordinary period of economic growth in US and Europe. Third, the invention of the microchip in 1969 brought about the IT revolution in the 1990s. The common metric for measuring innovation is productivity (total factor productivity, TFP, in economists' jargon), whose level is determined by how efficiently and intensively capital and labor are utilized in the production of goods and services (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Productivity growth comes in waves (yoy changes).

Data source: Bergeaud, A. et al. (2016). TFP from 1890 to 2022

Chart 1 plots the productivity growth in US and Europe between 1892 and 2022 and shows how the electricity revolution resulted in a "one big wave" of innovation, which originated in the US and spread to Europe in the aftermath of WWII. A period of rapid and sustained growth followed and quality of life radically improved. Since the first oil shock at the beginning of the 1970s, productivity growth started declining, with the exception of a short period linked to the IT revolution and to the diffusion of information and communication technologies in the 1990s. Following the Great Recession of 2008, productivity has fallen to historical lows in US and Europe despite the significant advances in the IT sector.

The grim decline in global productivity is difficult to reconcile with the spectacular wave of inventions that reshaped our daily lives: smartphones, social media platforms, cloud computing, CRISPR gene editing, electric vehicles, to name a few. Crucially, research indicates that the productivity slowdown in US and Europe cannot be explained by measurement errors in national statistics.

Business lethargy

What explains the US productivity slowdown?

A plausible argument is that the business dynamism in the US has weakened over time. The main reason is that leader firms in a specific sector discourage new innovation by potential entrants in their respective sectors - for instance, by acquiring patents for defensive purposes - , which make harder for potential entrants to catch up with the leaders. As a result of their investments in proprietary technologies and the concentration of intellectual property in their hands, leader firms consolidate their dominant position, earn higher markups and acquire a greater weight in the economy at the expense of innovation and economic growth.

The second argument, put forward by the economist Ken Arrow about 60 years ago, is that monopolistic firms have less incentive to innovate because their existing monopolistic rents are secure and innovation may put these profits at risk. Conversely, firms in competitive markets have greater incentives to innovate as they have more to gain from innovative technologies that could lead to monopolistic profits. Arrow's incentive to innovate works in the opposite direction of Schumpeter's incentive for entrepreneurs.

Symptoms of the weaker business dynamism in the US include the increase of market concentration, the increase of markups and profit share of GDP, the decline of labor share of output, the decline of firm entry rates, the decline of the economic share of young firms and the decrease of job reallocation.

In essence, market leaders, especially in the US tech sector, are less motivated to innovate whereas they rationally build artificial barriers that reduce the innovation ability of potential and actual rivals, explaining the fall of US productivity. Ultimately, the headwinds blowing against new, innovative companies affect the health of the entire economy. Consumers love tech firms' products, but technology might have morphed from a force driving disruption and competition into a force that obstruct progress and hinder economic growth.

Francesco Mandalà, PhD